Risk-First Analysis Framework

Start Here

Home

Contributing

Quick Summary

A Simple Scenario

The Risk Landscape

Discuss

Please star this project in GitHub to be invited to join the Risk First Organisation.

Publications

Click Here For Details

Feature Risk

Feature Risks are risks to do with functionality that you need to have in the software you’re building.

As a simple example, if your needs are served perfectly by Microsoft Excel, then you don’t have any Feature Risk. However, the day you find Microsoft Excel wanting, and decide to build an Add-On is the day when you first appreciate some Feature Risk. Now you’re a customer: does the Add-On you build satisfy the requirements you have?

Feature Risk is very fundamental: if there were no Feature Risk, the job would be done by Excel already and it would be perfect!

As we will explore below, Feature Risk exists in the gaps between what users want, and what they are given.

Not considering Feature Risk means that you might be building the wrong functionality, for the wrong audience or at the wrong time. And eventually, this will come down to lost money, business, acclaim, or whatever else reason you are doing your project for. So let’s unpack this concept into some of its variations.

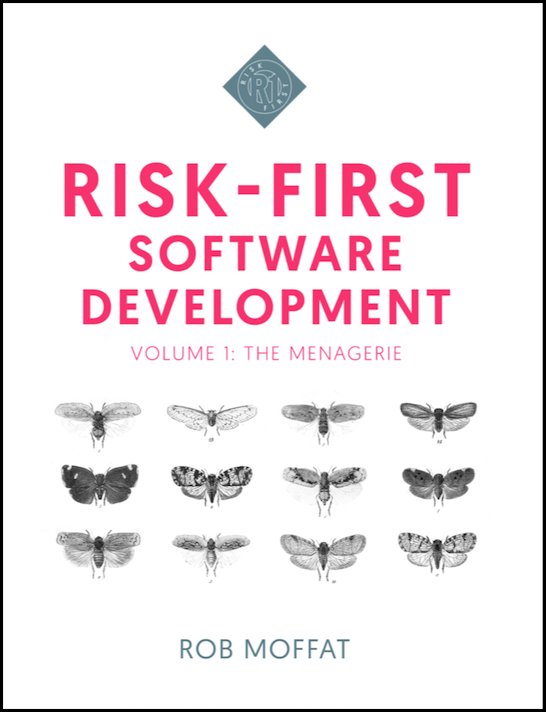

Feature Fit Risk

This is the one we’ve just discussed above - the feature that clients want to use in the software isn’t there:

- This might manifest itself as complete absence of something you need, e.g “Why is there no word count in this editor?”

- It could be that the implementation isn’t complete enough, e.g “why can’t I add really long numbers in this calculator?”

Feature Fit Risks are mitigated by talking to clients and building things, which leads on to…

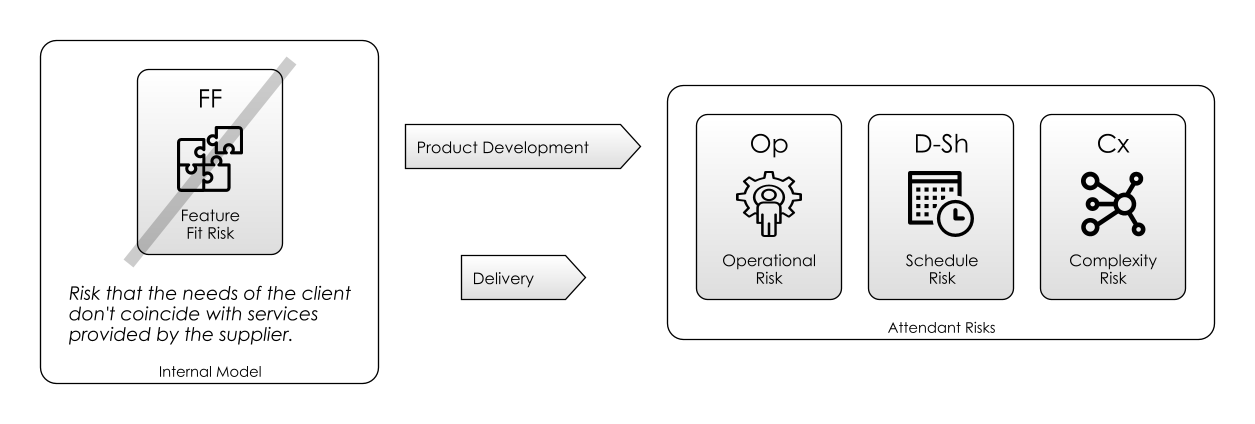

Implementation Risk

Feature Risk also includes things that don’t work as expected: that is to say, bugs. Although the distinction between “a missing feature” and “a broken feature” might be worth making in the development team, we can consider these both the same kind of risk: the software doesn’t do what the user expects.

At this point, it’s worth pointing out that sometimes, the user expects the wrong thing. This is a different but related risk, which could be down to training, documentation or simply a poor user interface (and we’ll look at that more in Communication Risk.)

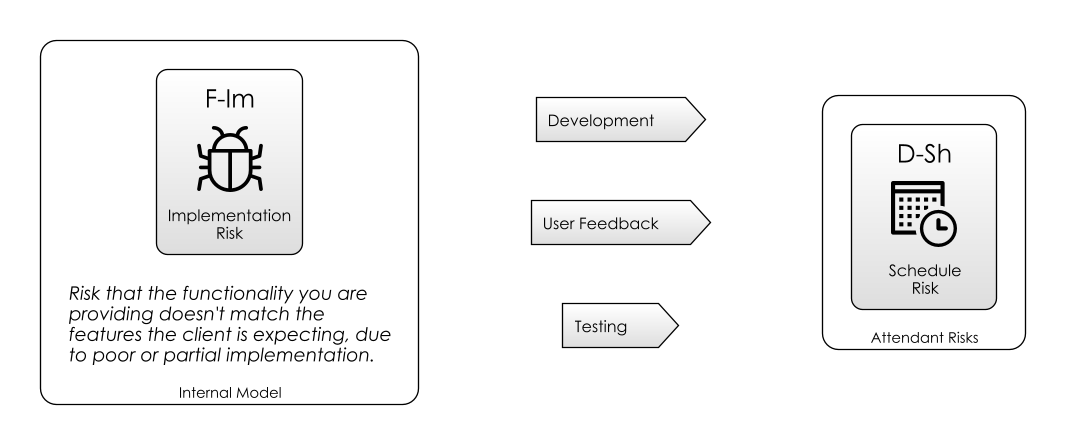

Regression Risk

Regression Risk is the risk of breaking existing features in your software when you add new ones. As with the previous risks, the eventual result is the same; customers don’t have the features they expect. This can become a problem as your code-base gains Complexity, as it becomes impossible to keep a complete Internal Model of the whole thing in your head.

Delivering new features can delight your customers, breaking existing ones will annoy them. This is something we’ll come back to in Operational Risk.

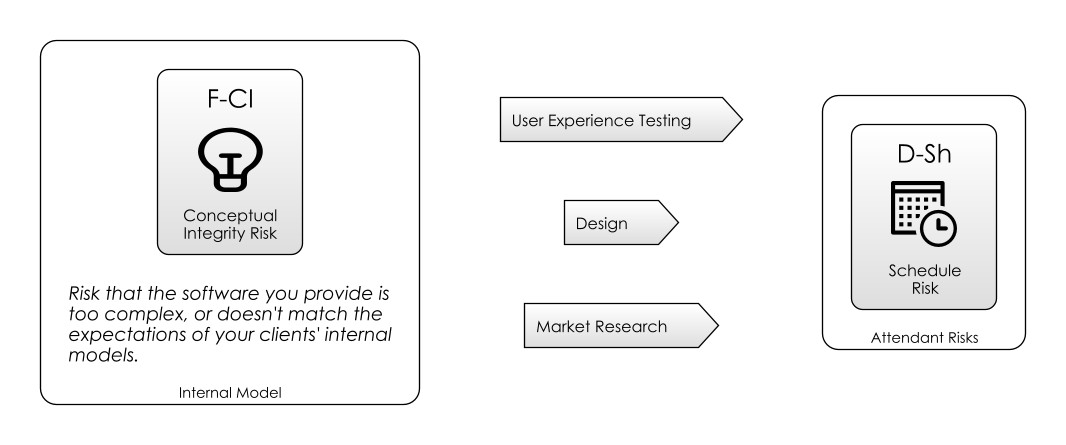

Conceptual Integrity Risk

Sometimes, users swear blind that they need some feature or other, but it runs at odds with the design of the system, and plain doesn’t make sense. Often, the development team can spot this kind of conceptual failure as soon as it enters the Backlog. Usually, it’s in coding that this becomes apparent.

Sometimes, it can go for a lot longer. I once worked on some software that was built as a score-board within a chat application. However, after we’d added much-asked-for commenting and reply features to our score-board, we realised we’d implemented a chat application within a chat application, and had wasted our time enormously.

Feature Phones are a real-life example: although it seemed like the market wanted more and more features added to their phones, Apple’s iPhone was able to steal huge market share by presenting a much more enjoyable, more coherent user experience, despite being more expensive and having fewer features. Feature Phones had been drowning in increasing Conceptual Integrity Risk without realising it.

This is a particularly pernicious kind of Feature Risk which can only be mitigated by good Design. Human needs are fractal in nature: the more you examine them, the more complexity you can find. The aim of a product is to capture some needs at a general level: you can’t hope to anticipate everything.

Conceptual Integrity Risk is the risk that chasing after features leaves the product making no sense, and therefore pleasing no-one.

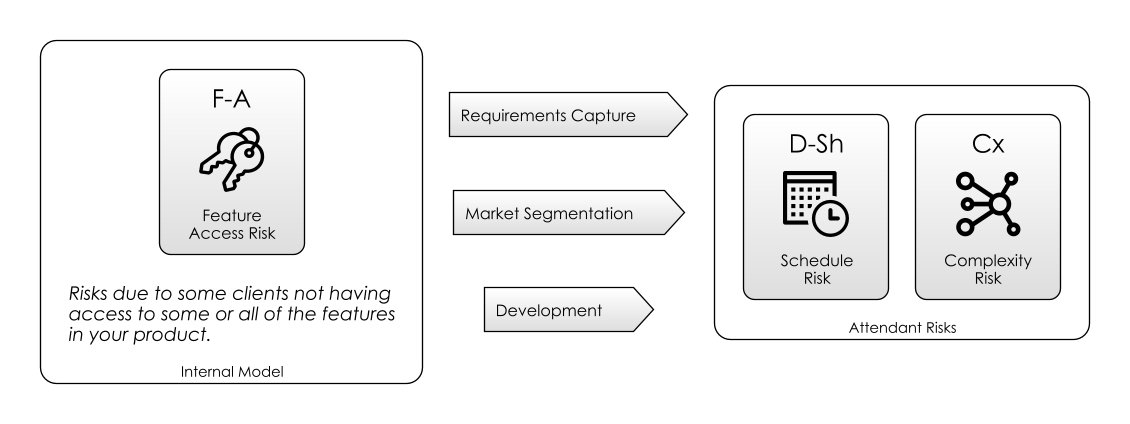

Feature Access Risk

Sometimes, features can work for some people and not others: this could be down to Accessibility issues, language barriers or localisation.

You could argue that the choice of platform is also going to limit access: writing code for XBox-only leaves PlayStation owners out in the cold. This is largely Feature Access Risk, though Dependency Risk is related here.

In marketing terms, minimising Feature Access Risk is all about Segmentation: trying to work out who your product is for, and tailoring it to that particular market. For developers, increasing Feature Access means increasing complexity: you have to deliver the software on more platforms, localised in more languages, with different configurations of features. Mitigating Feature Access Risk therefore means increased effort and complexity (which we’ll come to later).

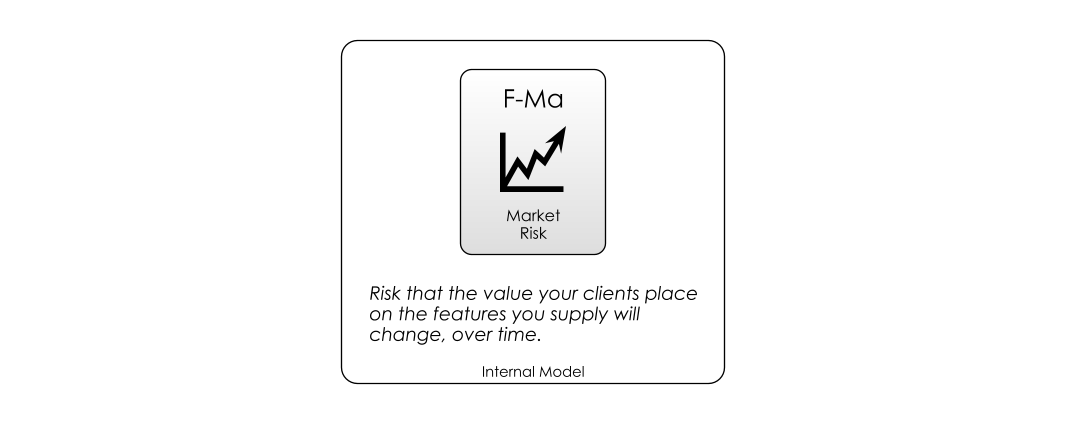

Market Risk

Feature Access Risk is related to Market Risk, which I introduced on the Risk Landscape page as being the value that the market places on a particular asset.

“Market risk is the risk of losses in positions arising from movements in market prices.” - Market Risk, Wikipedia

I face market risk when I own (i.e. have a position in) some Apple stock. Apple’s’s stock price will decline if a competitor brings out an amazing product, or if fashions change and people don’t want their products any more.

Since the product you are building is your asset, it makes sense that you’ll face Market Risk on it: the market decides what it is prepared to pay for this, and it tends to be outside your control.

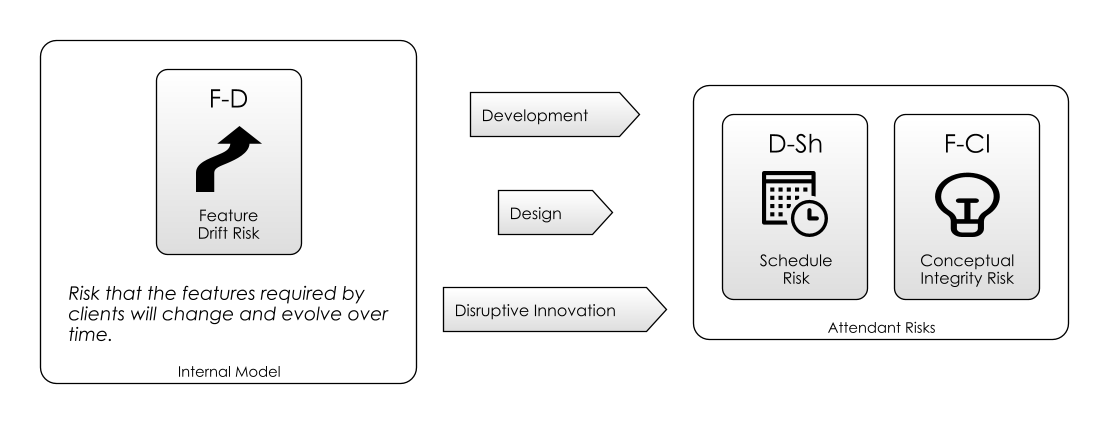

Feature Drift Risk

Feature Drift is the tendency that the features people need change over time. For example, at one point in time, supporting IE6 was right up there for website developers, but it’s not really relevant anymore. The continual improvements we see in processor speeds and storage capacity of our computers is another example: the Wii was hugely popular in the early 2000’s, but expectations have moved on now.

The point is: Requirements captured today might not make it to tomorrow, especially in the fast-paced world of IT. This is partly because the market evolves and becomes more discerning. This happens in several ways:

- Features present in competitor’s versions of the software become the baseline, and they’re expected to be available in your version.

- Certain ways of interacting become the norm (e.g. querty keyboards, or the control layout in cars: these don’t change with time).

- Features decline in usefulness: Printing is less important now than it was, for example.

As we will see later in Boundary Risk, Feature Drift Risk is often a source of Complexity Risk, since you often need to add new features, while not dismantling old features as some users still need them.

Feature Drift Risk is not the same thing as Requirements Drift, which is the tendency projects have to expand in scope as they go along. There are lots of reasons they do that, a key one being the Hidden Risks uncovered on the project as it progresses.

Fashion

Fashion plays a big part in IT. By being fashionable, web-sites are communicating: this is a new thing, this is relevant, this is not terrible: all of which is mitigating a Communication Risk. Users are all-too-aware that the Internet is awash with terrible, abandon-ware sites that are going to waste their time. How can you communicate that you’re not one of them to your users?

Delight

If this breakdown of Feature Risk seems reductive, then try not to think of it that way: the aim of course should be to delight users, and turn them into fans.

Consider Feature Risk from both the down-side and the up-side:

- What are we missing?

- How can we be even better?

Analysis

So far in this section, we’ve simply seen a bunch of different types of Feature Risk. But we’re going to be relying heavily on Feature Risk as we go on in order to build our understanding of other risks, so it’s probably worth spending a bit of time up front to classify what we’ve found.

The Feature Risks identified here basically exist in a space with at least 3 dimensions:

- Fit: how well the features fit for a particular client.

- Audience: the range of clients (the market) that may be able to use this feature.

- Evolution: the way the fit and the audience changes and evolves as time goes by.

Let’s examine each in turn.

Fit

“This preservation, during the battle for life, of varieties which possess any advantage in structure, constitution, or instinct, I have called Natural Selection; and Mr. Herbert Spencer has well expressed the same idea by the Survival of the Fittest” - Charles Darwin (Survival of the Fittest), Wikipedia.

Darwin’s conception of fitness was not one of athletic prowess, but how well an organism worked within the landscape, with the goal of reproducing itself.

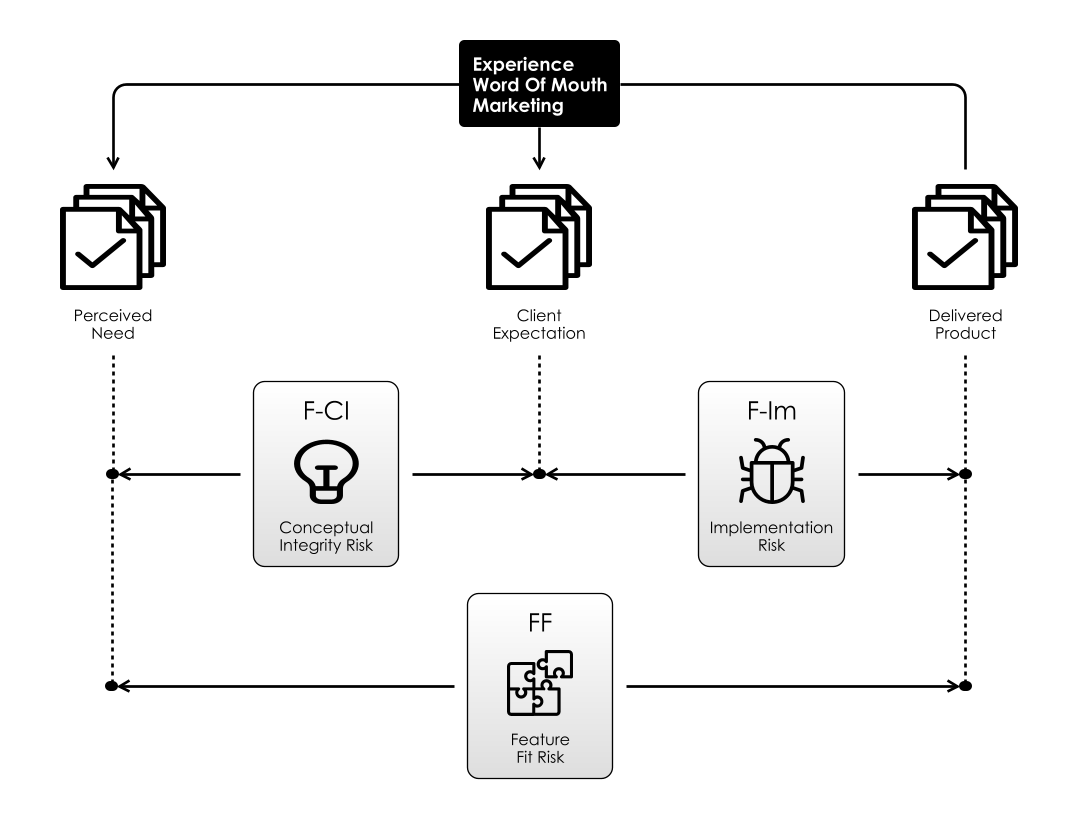

Feature Fit Risk, Conceptual Integrity Risk and Implementation Risk all hint at different aspects of this “fitness”. We can conceive of them as the gaps between the following entities:

- Perceived Need: what the developers think the users want.

- Expectation: what the user expects.

- Reality: what they actually get.

For further reading, you can check out The Service Quality Model, which the diagram above is derived from. This model analyses the types of quality gaps in services and how consumer expectations and perceptions of a service arise.

In the Staging And Classifying section, we’ll come back and build on this model further.

Fit and Audience

Two risks, Feature Access Risk and Market Risk considers Fit for a whole Audience of users. They are different: just as it’s possible to have a small audience, but a large revenue, it’s possible to have a product which has low Feature Access Risk (i.e lots of users can access it without difficulty) but high Market Risk (i.e. the market is highly volatile or capricious in it’s demands). Online services often suffer from this Market Risk roller-coaster, being one moment highly valued and the next irrelevant.

- Market Risk is therefore risk to income from the market changing.

- Feature Access Risk is risk to audience changing.

Fit, Audience and Evolution

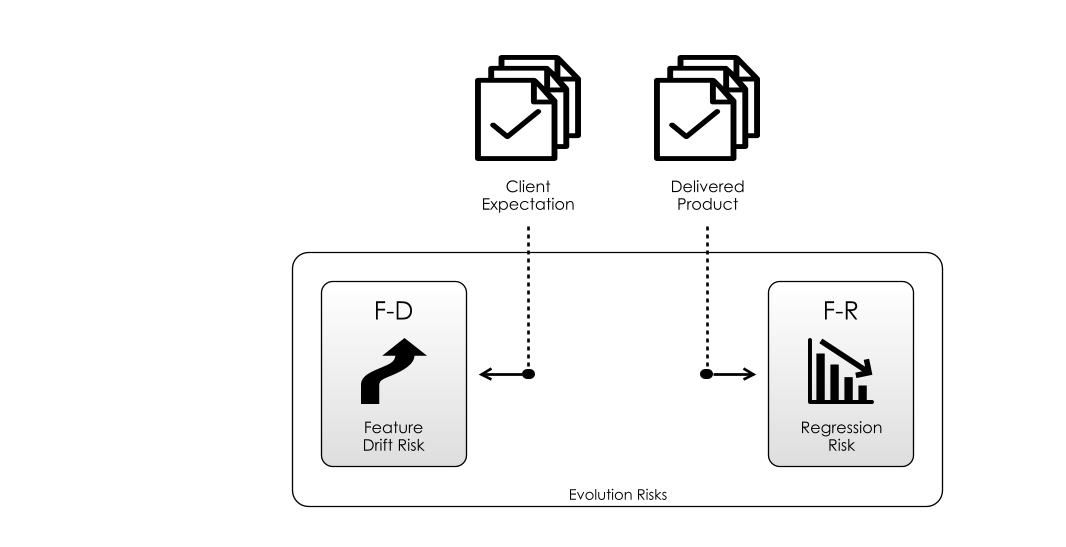

Two risks further consider how the Fit and Audience change: Regression Risk and Feature Drift Risk. We call this evolution in the sense that:

- Our product’s features evolve with time and changes made by the development team.

- Our audience changes and evolves as it is exposed to our product and competing products.

- The world as a whole is an evolving system within which our product exists.

Applying Feature Risk

Next time you are grooming the backlog, why not apply this:

- Can you judge which tasks mitigate the most Feature Risk?

- Are you delivering features that are valuable across a large audience? Or of less value across a wider audience?

- How does writing a specification mitigate Fit Risk? For what other reasons are you writing specifications?

- Does the audience know that the features exist? How do you communicate feature availability to them?

In the next section, we are going to unpack this last point further. Somewhere between “what the customer wants” and “what you give them” is a dialog. In using a software product, users are engaging in a dialog with its features. If the features don’t exist, hopefully they will engage in a dialog with the development team to get them added.

These dialogs are prone to risk and this is the subject of the next section, Communication Risk.