Risk-First Analysis Framework

Start Here

Home

Contributing

Quick Summary

A Simple Scenario

The Risk Landscape

Discuss

Please star this project in GitHub to be invited to join the Risk First Organisation.

Publications

Click Here For Details

Operational Risk

“The risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events.” - Operational Risk, Wikipedia

In this section we’re going to start considering the realities of running software systems in the real world.

There is a lot to this subject, so this section is really offers just a taster: we’re going to set the scene by looking at what constitutes an Operational Risk, and then look at the related discipline of Operations Management. Following this background, we’ll apply the Risk-First model and have a high-level look at the various mitigations for Operational Risk.

Operational Risks

When building software, it’s tempting to take a very narrow view of the dependencies of a system, but Operational Risks are often caused by dependencies we don’t consider - i.e. the Operational Context within which the system is operating. Here are some examples:

- Staff Risks:

- Freak weather conditions affecting ability of staff to get to work, interrupting the development and support teams.

- Reputational damage caused when staff are rude to the customers.

- Reliability Risks:

- A data-centre going off-line, causing your customers to lose access.

- A power cut causing backups to fail.

- Not having enough desks for everyone to sit at.

- Process Risks:

- Regulatory change, which means you have to adapt your business model.

- Insufficient controls which means you don’t notice when some transactions are failing, leaving you out-of-pocket.

- Data loss because of bugs introduced during an untested release.

- Software Dependency Risk:

- Hackers exploit weaknesses in a piece of 3rd party software, bringing your service down.

- Agency Risk:

- Workers going on strike.

- Employees trying to steal from the company (bad actors).

- Other crime, such as hackers stealing data.

This is a long laundry-list of everything that can go wrong due to operating in “The Real World”. Although we’ve spent a lot of time looking at the varieties of Dependency Risk on a software project, with Operational Risk we have to consider that these dependencies will fail in any number of unusual ways, and we can’t be ready for all of them. Nevertheless, preparing for this comes under the umbrella of Operations Management.

Operations Management

If we are designing a software system to “live” in the real world, we have to be mindful of the Operational Context we’re working in, and craft our software and processes accordingly. This view of the “wider” system is the discipline of Operations Management.

“Operations management is an area of management concerned with designing and controlling the process of production and redesigning business operations in the production of goods or services. It involves the responsibility of ensuring that business operations are efficient in terms of using as few resources as needed and effective in terms of meeting customer requirements. “ - Operations Management, Wikipedia

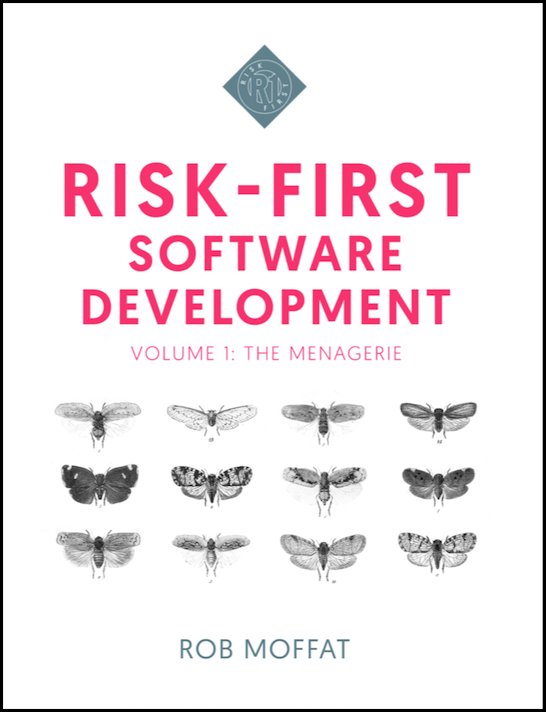

The diagram above is a Risk-First interpretation of Slack et al’s model of Operations Management. This model breaks down some of the key abstractions of the discipline:

- A Transform Process (the Operation itself), which tries to achieve an…

- Operational Strategy (the objectives of the operation) and is embedded in the wider…

- Operational Context.

The Operational Context supplies the Transform Process with three key dependencies:

- Resources: whether transformed resources (like electricity or information, say) or transforming resources (like staff or equipment).

- Customers: which supply it with money in return for goods and services.

- Operational Strategy: the goals and objectives of the operation, informed by the reality of the environment it operates in.

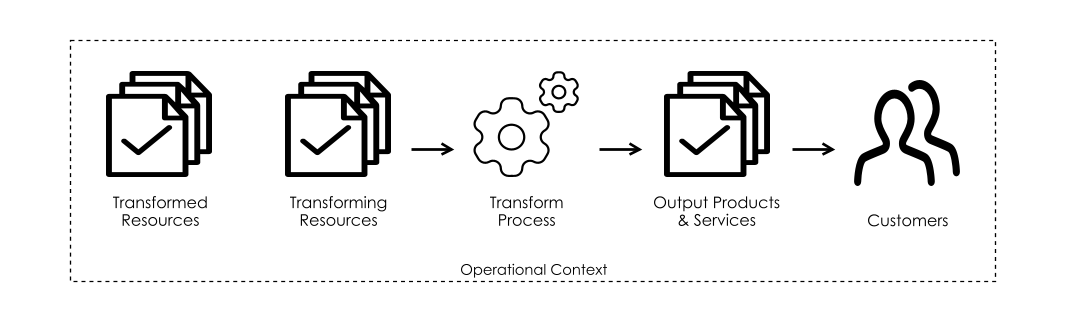

We have looked at processes like the Transform Process in the section on Process Risk. The healthy functioning of this process is the domain of Operations Management. As the above diagram shows (again, modified from Slack et al.) this involves the following types of actions:

- Control: ensuring that the Operation is working according to its targets. This includes day-to-day quality control and monitoring of the Transform Process.

- Planning: this covers aspects such as capacity planning, forecasting and project planning. This is about making sure the transform process has targets to meet and the resources to meet them.

- Design: ensuring that the design of the product and the transform process itself fulfils an Operational Strategy.

- Improvement: improving the operation in response to changes in the Environment and the Operational Strategy, detecting failure and recovering from it.

Let’s look at each of these actions in turn.

Control

Since humans and machines have different areas of expertise, and because Operational Risks are often novel, it’s often not optimal to try and automate everything. A good operation will consist of a mix of human and machine actors, each playing to their strengths (see the table below).

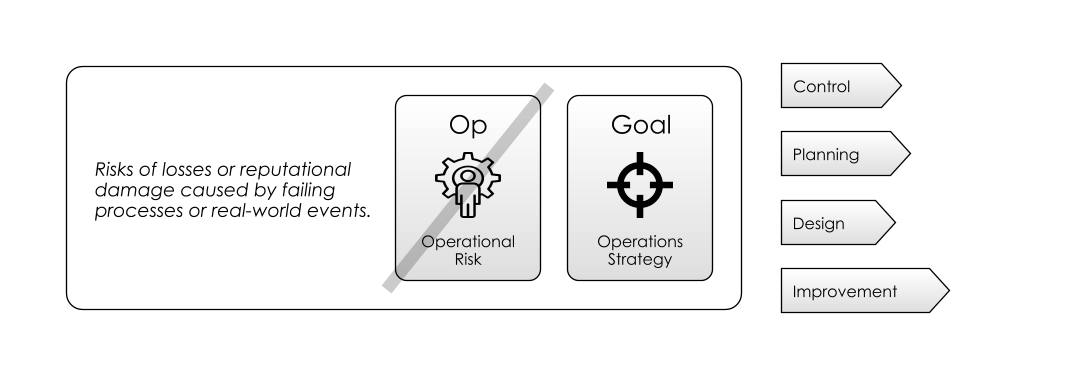

The aim is to build a human-machine operational system that is Homeostatic. This is the property of living things to try and maintain an equilibrium (for example, body temperature or blood glucose levels), but also applies to systems at any scale. The key to homeostasis is to build systems with feedback loops, even though this leads to more complex systems overall. The diagram above shows some of the actions involved in these kind of feedback loops.

| Humans Are… | Machines Are… |

|---|---|

| Good at novel situations | Good at repetitive situations |

| Good at adaptation | Good at consistency |

| Expensive at scale | Cheap at scale |

| Reacting and Anticipating | Recording |

As we saw in Map and Territory Risk, it’s very easy to fool yourself, especially around Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and metrics. Large organisations have Audit functions precisely to guard against their own internal failing processes and Agency Risk. Audits could be around software tools, processes, practices, quality and so on. Practices such as Continuous Improvement and Total Quality Management also figure here.

Scanning The Operational Context

There are plenty of Hidden Risks within the environment the operation exists within, and these change all the time in response to economic, legal or political change. In order to manage a risk, you have to uncover it, so part of Operations Management is to look for trouble:

- Environmental Scanning is all about trying to determine which changes in the environment are going to impact your operation. Here, we are trying to determine the level of Dependency Risk we face for external dependencies, such as suppliers, customers, markets and regulation. Tools like PEST are relevant here, as is

- Penetration Testing is looking for security weaknesses within the operation. See OWASP for examples.

- Vulnerability Management is keeping up-to-date with vulnerabilities in Software Dependencies.

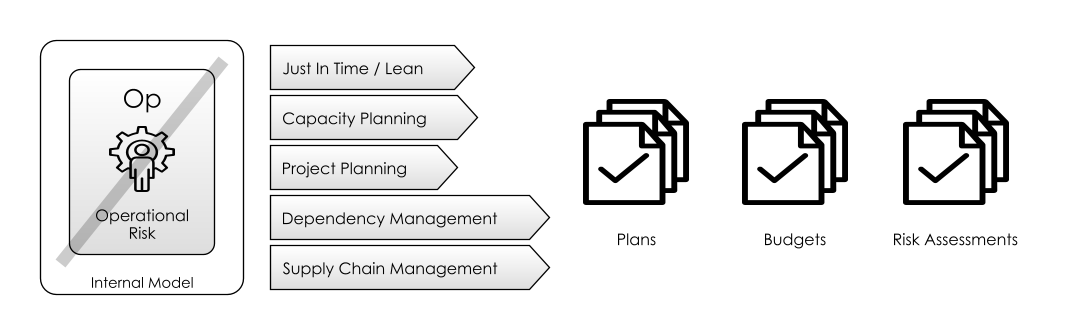

Planning

In order to control an operation, we need targets and plans to control against. For a system to run well, it needs to carefully manage unreliable dependencies, and ensure their safety and availability. In the example of the humans, say, it’s the difference between Hunter-Gathering (picking up food where we find it) and Agriculture (controlling the environment and the resources to grown crops).

As the diagram above shows, we can bring Planning to bear on dependency management, and this usually falls to the more human end of the operation.

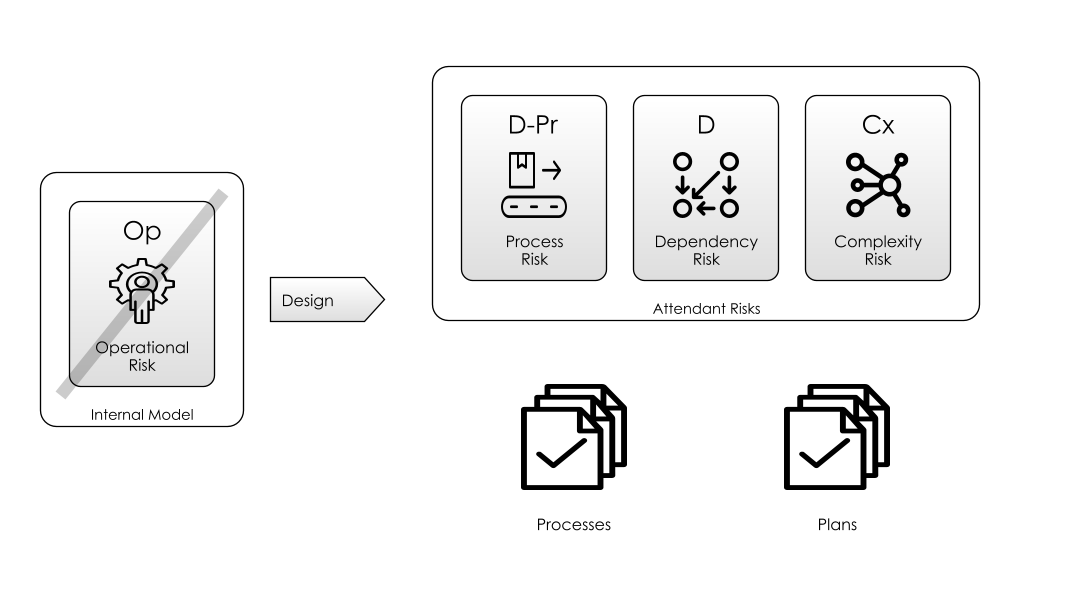

Design

Since our operation exists in a world of risks like Red Queen Risk and Feature Drift Risk, we would expect that the output of our Planning actions would result in changes to our operation.

While planning is a day-to-day operational feedback loop, design is a longer feedback loop changing not just the parameters of the operation, but the operation itself.

You might think that for an IT operation, tasks like Design belong within a separate “Development” function within an organisation. Traditionally, this might have been the case. However separating Development from Operation implies Boundary Risk between these two functions. For example, the developers might employ different tools, equipment and processes to the operations team, resulting in a mismatch when software is delivered.

In recent years, the DevOps movement has brought this Boundary Risk into sharper focus. This specifically means:

- Using code to automate previously manual Operations functions, like monitoring and releasing.

- Involving Operations in the planning and design, so that the delivered software is optimised for the environment it runs in.

Improvement

No system can be perfect, and after it meets the real world, we will want to improve it over time. But Operational Risk includes an element of Trust & Belief Risk: we have a reputation and the good will of our customers to consider when we make improvements. Because this is very hard to rebuild, we should consider this before releasing software that might not live up to expectations.

So there is a tension between “you only get one chance to make a first impression” and “gilding the lily” (perfectionism). In the past I’ve seen this stated as:

“Pressure to ship vs pressure to improve”

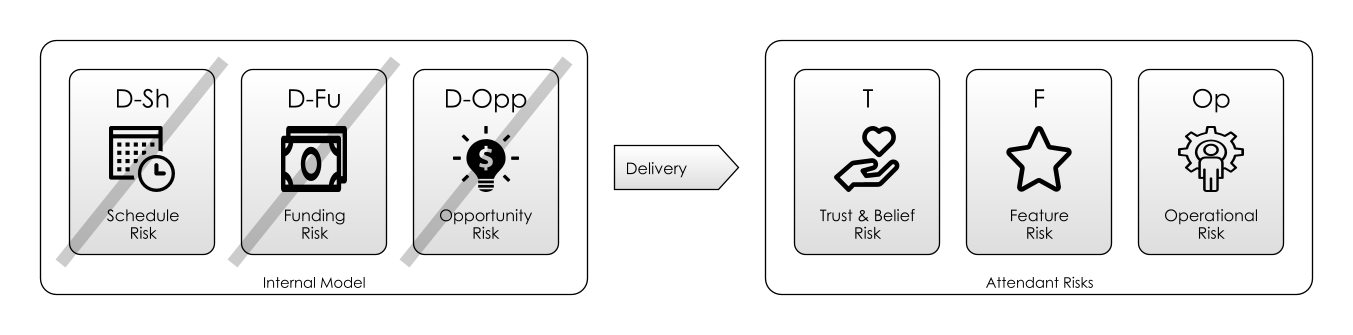

A Risk-First re-framing of this (as shown in the diagram above) might be the balance between:

- The perceived Scarcity Risks (such as funding, time available, etc) of staying in development (pressure to ship).

- The perceived Trust & Belief Risk, Feature Risk and Operational Risk of going to production (pressure to improve).

The “should we ship?” decision is therefore a complex one. In Meeting Reality, we discussed that it’s better to do this “sooner, more frequently, in smaller chunks and with feedback”. We can meet Operational Risk on our own terms by doing so:

| Meet Reality… | Techniques |

|---|---|

| Sooner | Quality Control Processes, Limited Early-Access Programs, Beta Programs, Soft Launches, Business Continuity Testing |

| More Frequently | Continuous Delivery, Sprints |

| In Smaller Chunks | Modular Releases, Microservices, Feature Toggles, Trial Populations |

| With Feedback | User Communities, Support Groups, Monitoring, Logging, Analytics |

End Of The Road

In a way, actions like Design and Improvement bring us right back to where we started from: identifying Dependency Risks, Feature Risks and Complexity Risks that hinder our operation, and mitigating them through actions like software development.

Our safari of risk is finally complete, it’s time to look back and what we’ve seen in Staging and Classifying.