Risk-First Analysis Framework

Start Here

Home

Contributing

Quick Summary

A Simple Scenario

The Risk Landscape

Discuss

Please star this project in GitHub to be invited to join the Risk First Organisation.

Publications

Click Here For Details

Process Risk

Process Risk, as we will see, is the risk you take on whenever you embark on completing a process.

“Process: a process is a set of activities that interact to achieve a result.” - Process, Wikipedia

Processes commonly involve forms: if you’re filling out a form (whether on paper or on a computer) then you’re involved in a process of some sort, whether an “Account Registration” process, “Loan Application” process or “Consumer Satisfaction Survey” process. Sometimes, they involve events occurring: a build process might start after you commit some code, for example. And, the code we write is usually describing some kind of process we want performed.

The Purpose Of Process

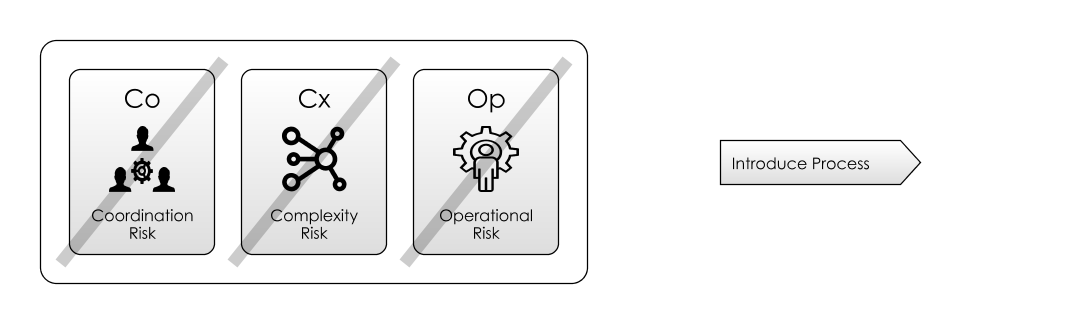

As the above diagram shows, process exists to mitigate other kinds of risk. For example:

- Coordination Risk: you can often use process to help people coordinate. For example, a Production Line is a process where work being done by one person is pushed to the next person when it’s done. A meeting booking process is designed to efficiently allocate meeting rooms.

- Operational Risk: this encompasses the risk of people not doing their job properly. But, by having a process, (and asking, did this person follow the process?) you can draw a distinction between a process failure and a personnel failure. For example, making a loan to a money launderer could be a failure of the loan agent. But, if they followed the process, it’s a failure of the Process itself.

- Complexity Risk: working within a process can reduce the amount of Complexity you have to think about. We accept that processes are going to slow us down, but we appreciate the reduction in risk this brings. Clearly, the complexity hasn’t gone away, but it’s hidden within design of the process. For example, McDonalds tries to design its operation so that preparing each food item is a simple process to follow, reducing complexity (and training time) for the staff.

These are all examples of Risk Mitigation for the owners of the process. But often the consumers of the process end up picking up Process Risks as a result:

- Invisibility Risk: it’s often not possible to see how far along a process is to completion. Sometimes, you can do this to an extent. For example, when I send a package for delivery, I can see roughly how far it’s got on the tracking website. But, this is still less-than-complete information, and is a representation of reality.

- Dead-End Risk: even if you have the right process, initiating a process has no guarantee that your efforts won’t be wasted and you’ll be back where you started from. The chances of this happening increase as you get further from the standard use-case for the process, and the sunk cost increases with the length of time the process takes to complete.

- Feature Access Risk: processes generally handle the common stuff, but ignore the edge cases. For example, a form on a website might not be designed to be accessible to disabled people, or might only cater to some common subset of use-cases.

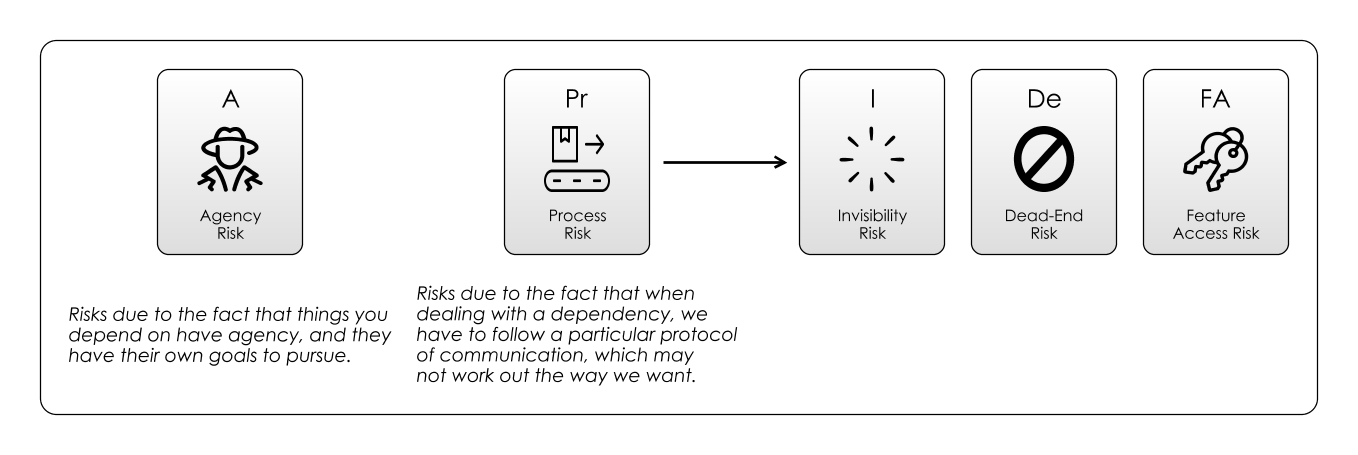

When we talk about “Process Risk” we are really referring to these types of risks, arising from “following a set of instructions.” Compare this with Agency Risk (which we will review in a forthcoming section), which is risks due to not following the instructions, as shown in the above diagram . Let’s look at two examples, how Process Risk can lead to Invisibility Risks and Agency Risk.

Processes And Invisibility Risk

Processes tend to work well for the common cases, because practice makes perfect. but they are really tested when unusual situations occur. Expanding processes to deal with edge-cases incurs Complexity Risk, so often it’s better to try and have clear boundaries of what is “in” and “out” of the process’ domain.

Sometimes, processes are not used commonly. How can we rely on them anyway? Usually, the answer is to build in extra feedback loops anyway:

- Testing that backups work, even when no backup is needed.

- Running through a disaster recovery scenario at the weekend.

- Increasing the release cadence, so that we practice the release process more.

The feedback loops allow us to perform Retrospectives and Reviews to improve our processes.

Processes, Sign-Offs and Agency Risk

Often, Processes will include sign-off steps. The Sign-Off is an interesting mechanism:

- By signing off on something for the business, people are usually in some part staking their reputation on something being right.

- Therefore, you would expect that sign-off involves a lot of Agency Risk: people don’t want to expose themselves in career-limiting ways.

- Therefore, the bigger the risk they are being asked to swallow, the more cumbersome and protracted the sign off process.

Often, Sign Offs boil down to a balance of risk for the signer: on the one hand, personal, career risk from signing off, on the other, the risk of upsetting the rest of the staff waiting for the sign-off, and the Dead End Risk of all the effort gone into getting the sign off if they don’t.

This is a nasty situation, but there are a couple of ways to de-risk this:

- Break Sign Offs down into bite-size chunks of risk that are acceptable to those doing the sign-off.

- Agree far-in-advance the sign-off criteria. As discussed in Risk Theory, people have a habit of heavily discounting future risk, and it’s much easier to get agreement on the criteria than it is to get the sign-off.

Evolution Of Process

Writing software and designing processes are often overlapping activities. Often, we build processes when we are writing software. Since designing a process is an activity like any other on a project, you can expect that the Risk-First explanation for why we do this is risk management.

Processes arise because of a desire to mitigate risk. When whole organisations follow that desire independently, we end up in an evolutionary or gradient-descent style scenario of risk reduction (as we will see below).

Here, we are going to look at how a Business Process might mature within an organisation.

“Business Process or Business Method is a collection of related, structured activities or tasks that in a specific sequence produces a service or product (serves a particular business goal) for a particular customer or customers.” - Business Process, Wikipedia

Let’s look at an example of how that can happen in a step-wise way.

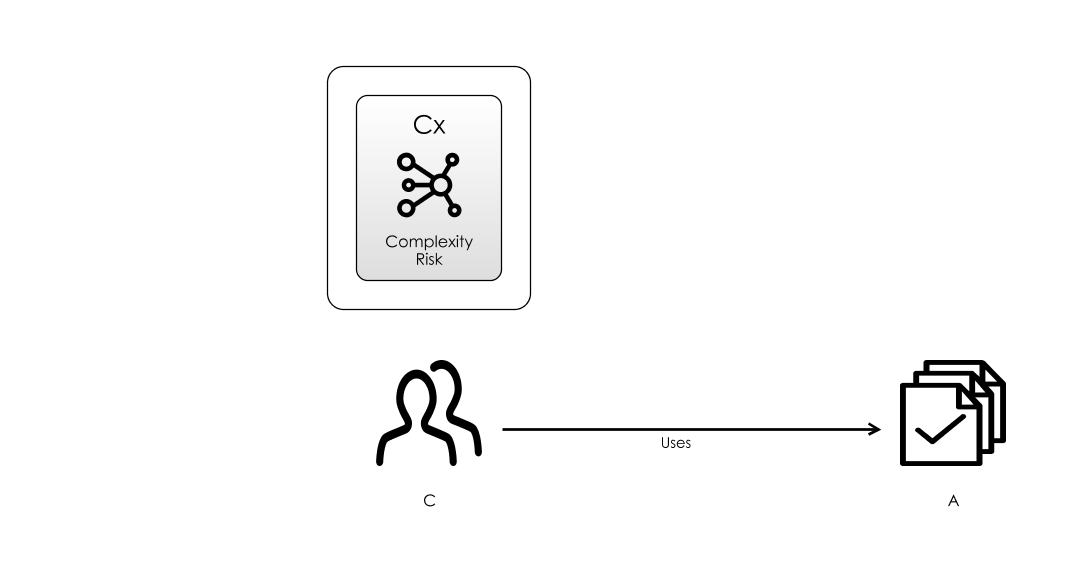

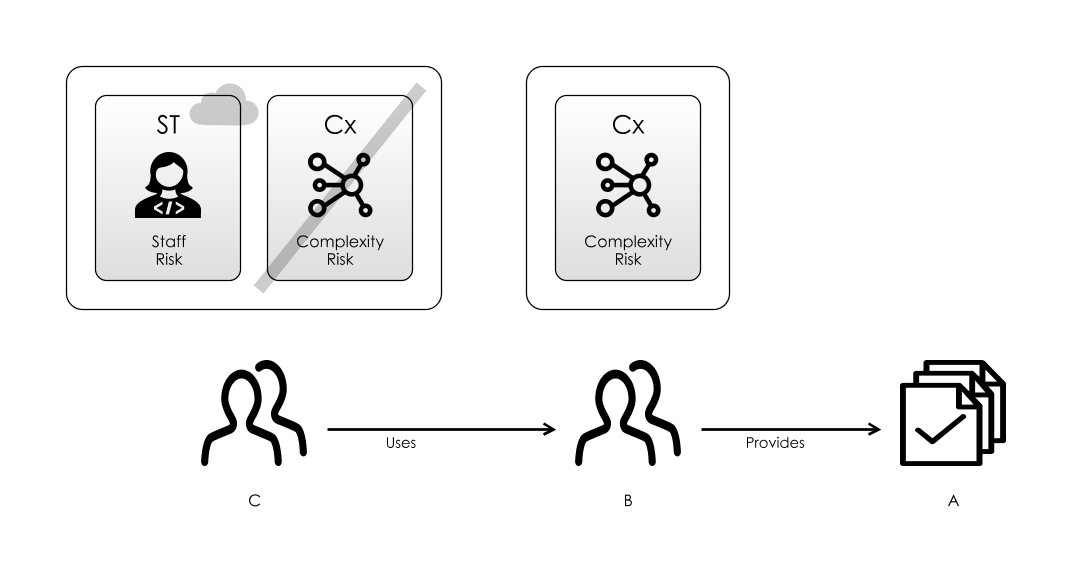

- As the above diagram shows, there exists a group of people inside a company

C, which need a certain somethingAin order to get their jobs done. Because they are organising, providing and creatingAto do their jobs, they are responsible for all the Complexity Risk ofA. The harder it is for them to secureA, the higher the risk.

- Because

Ais so complex, a new team (B) is spun up to deal with the Complexity Risk, which letsCget on with their “proper” jobs. As shown in the diagram above, this is really useful: It makesC’s job much easier (reduced Complexity Risk) as they have an easier path toAthan before. But the risk forAhasn’t really gone - they’re now just dependent onBinstead. When members ofBfail to deliver, this is Staff Risk forC.

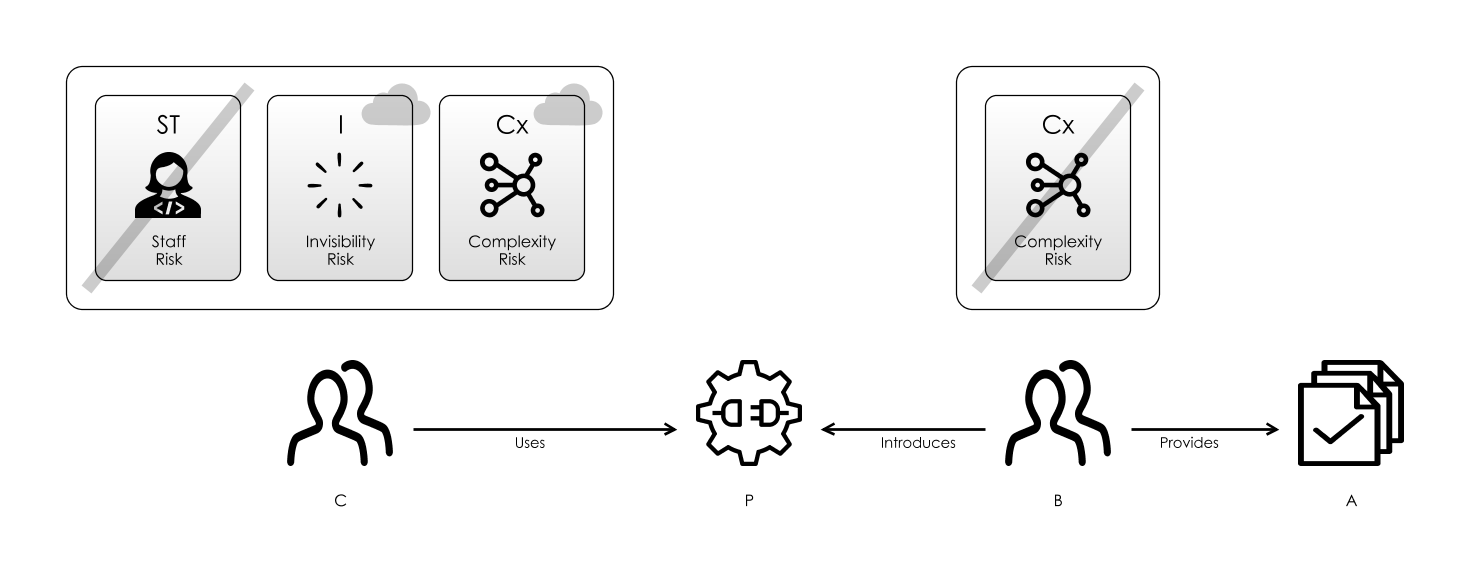

- Problems are likely to occur eventually in the

B/Crelationship. Perhaps some members of theBteam give better service than others, or deal with more variety in requests. In order to standardise the response fromB, and also to reduce scope-creep in requests fromC,Borganises bureaucratically, so that there is a controlled process (P) by whichAcan be accessed. Members of teamsBandCnow interact via some request mechanism like forms (or another protocol).

- As shown in the above diagram, because of

P,Bcan now deal with requests on a first-come-first-served basis and deal with them all in the same way: the more unusual requests fromCmight not fit the model. These Complexity Risks are now the problem of the form-filler inC. - Since this is Abstraction,

Cnow has Invisibility Risk since it can’t access teamBand see how it works. - Team

Bmay also usePto introduce other bureaucracy like authorisation and sign-off steps or payment barriers. All of this increases complexity for team C.

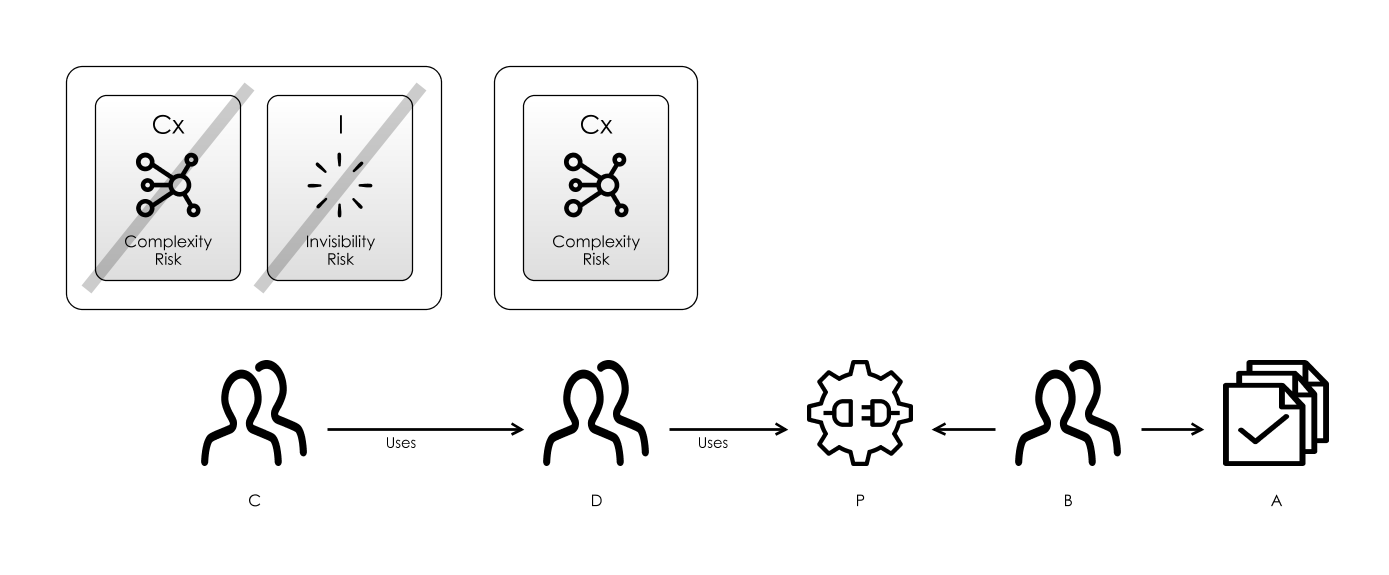

- Teams like

Bcan sometimes end up in “Monopoly” positions within a business. This means that clients likeCare forced to deal with whatever processBwishes to enforce. Although they are unable to affect processP,Cstill have risks they want to transfer.

- In the above diagram, Person

D, who has experience working with teamBacts as a middleman for some ofC, requiring some variant ofA. They are able to help navigate the bureaucratic process (handle with Process Risk). - The cycle potentially starts again: will

Dend up becoming a new team, with a new process?

In this example, you can see how the organisation evolves process to mitigate risk around the use (and misuse) of A. This is an example of Process following Strategy:

In this conception, you can see how the structure of an organisation (the teams and processes within it, the hierarchy of control) will ‘evolve’ from the resources of the organisation and the strategy it pursues. Processes evolve to meet the needs of the organisation.” - Henry Minzberg, Strategy Safari

Two key take-aways from this:

- The Process Gets More Complex: with different teams working to mitigate different risks in different ways, we end up with a more complex situation than we started in. Although we’ve evolved in this direction by mitigating risks, it’s not necessarily the case that the end result is more efficient. In fact, as we will see in Map-And-Territory Risk, this evolution can lead to some very inadequate (but nonetheless stable) systems.

- Organisational process evolves to mitigate risk: just as we’ve shown that actions are about mitigating risk, we’ve now seen that these actions get taken in an evolutionary way. That is, there is “pressure” on our internal processes to reduce risk. The people maintaining these processes feel the risk, and modify their processes in response. Let’s look at a real-life example:

An Example - Release Processes

For many years I have worked in the Finance Industry, and it’s given me time to observe how, across an entire industry, process can evolve, both in response to regulatory pressure but also because of organisational maturity, and mitigating risks:

- Initially, I could release software by logging onto the production accounts with a shared password that everyone knew, and deploy software or change data in the database.

- The first issue with this is Agency Risk from bad actors: how could you know that the numbers weren’t being altered in the databases? Production Auditing was introduced so that at least you could tell what was being changed and when, in order to point the blame later.

- But, there was still plenty of scope for deliberate or accidental Dead-End Risk damage. Next, passwords were taken out of the hands of developers and you needed approval to “break glass” to get onto production.

- The increasing complexity (and therefore Complexity Risk) in production environments meant that sometimes, changes collided with each other, or were performed at inopportune times. Change Requests were introduced. This is an approval process which asks you to describe what you want to change in production, and why you want to change it.

- The change request software is generally awful, making the job of raising change requests tedious and time-consuming. Therefore, developers would automate the processes for release, sometimes including the process to write the change request. This allowed them to improve release cadence, at the expense of owning more code.

- Auditors didn’t like the fact that this automation existed, because effectively, that meant that developers could get access to production with the press of a button, effectively taking you back to step 1…

Bureaucracy Risk

Where we’ve talked about process evolution above, the actors involved have been acting in good faith: they are working to mitigate risk in the organisation. The Process Risk that accretes along the way is an unintended consequence: There is no guarantee that the process that arises will be humane and intuitive. Many organisational processes end up being baroque or Kafka-esque, forcing unintuitive behaviour on their users. This is partly because process design is hard, and it’s difficult to anticipate all the various ways a process will be used ahead-of-time.

But Parkinson’s Law takes this one step further: the human actors shaping the organisation will abuse their positions of power in order to further their own careers (this is Agency Risk, which we will come to in a future section):

“Parkinson’s law is the adage that “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion”. It is sometimes applied to the growth of bureaucracy in an organisation… He explains this growth by two forces: (1) ‘An official wants to multiply subordinates, not rivals’ and (2) ‘Officials make work for each other.’” - Parkinson’s Law, Wikipedia

This implies that there is a tendency for organisations to end up with needless levels of Process Risk.

To fix this, design needs to happen at a higher level. In our code, we would Refactor these processes to remove the unwanted complexity. In an business, it requires re-organisation at a higher level to redefine the boundaries and responsibilities between the teams.

Next in the tour of Dependency Risks, it’s time to look at Boundary Risk.